Joseph Schumpeter was one of the world’s greatest economists, noteworthy not least for his thinking on Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Austrian born, Schumpeter was a Professor at Harvard University for almost 20 years. His best-known work “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” remains relevant today, despite first being published nearly 80 years ago. Schumpeter wrote that “in general, it is not the owners of stage coaches who build railways”. History is full of examples of businesses or, indeed, whole industries that failed to catch the next wave. The most value-destructive examples include Nokia’s failure to make smartphones, Kodak and digital cameras, Blockbuster and streaming. So is it inevitable that large and profitable businesses eventually fail? Put another way, can large existing organisations innovate?

These questions are as pertinent to the UK Military as they are to commercial businesses. Collectively, the UK Armed Forces are a large enterprise, successful in many ways. However, with some exceptions, this enterprise has not proved to be an early adopter of digital technology. Its acquisition system is risk averse, and therefore slower, and, very likely, more costly than it might be were more risk taken. And there are plenty of examples of opponents, often with far less resource, innovating to its detriment. Indeed, it could be argued that the UK Armed Forces have responded to these competitors in precisely the way that management thinker Clayton Christensen predicted, moving upmarket into more and more exquisite technology and focussing on sustaining innovations. The analogy between the UK military and large incumbent businesses can only be taken so far, not least because the definition of its customers is complex, its motives are not financial, and it is certainly capable of innovation, usually when it is under extreme pressure. But in my experience, 20 years of which have been spent directly grappling with the issue of innovation, from an array of vantage points at senior levels within the Ministry of Defence (eg planner, requirement setter, fleet manager, acquirer, and user), it struggles to innovate systemically.

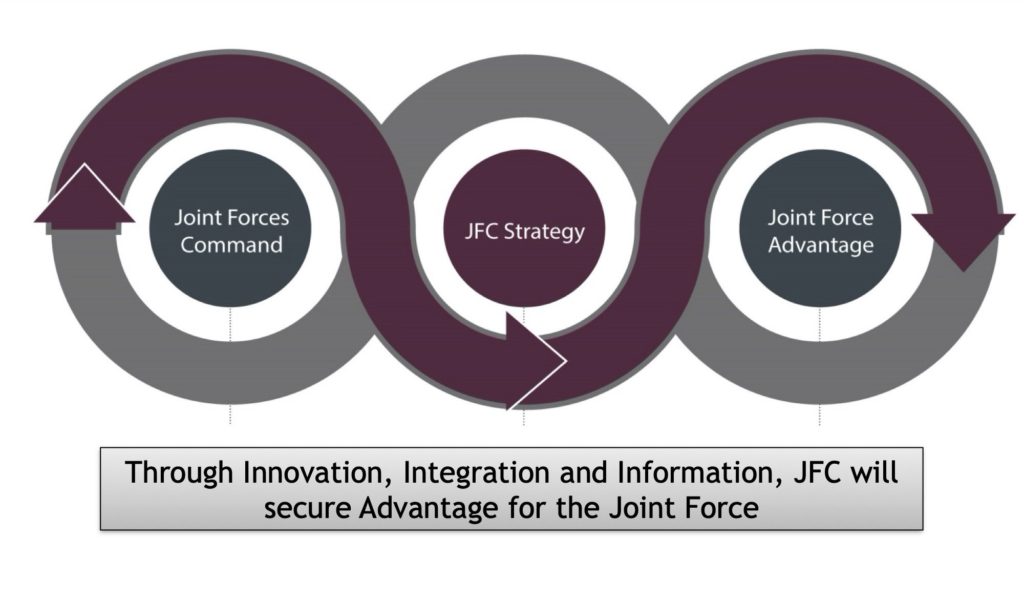

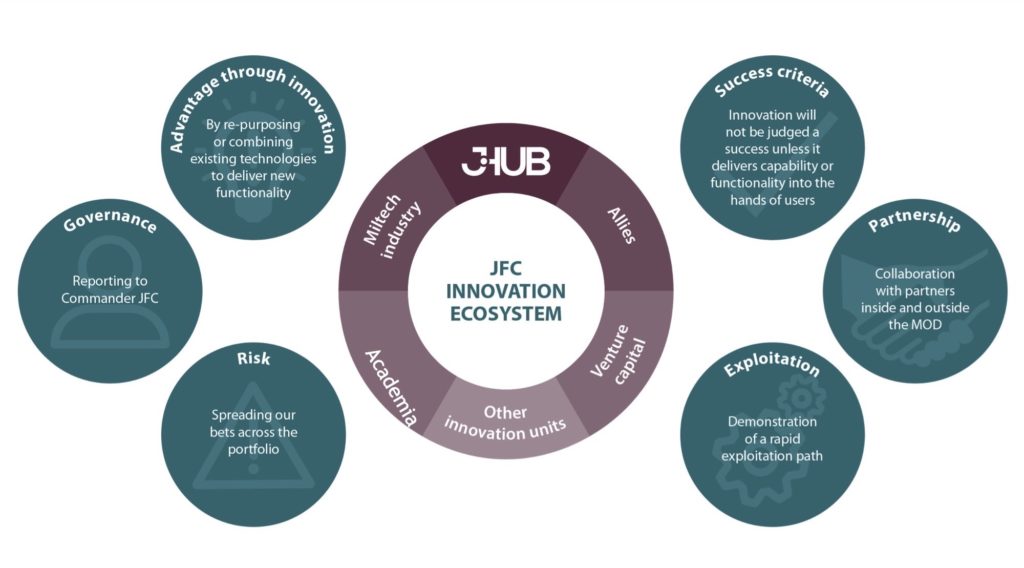

Acknowledging this during strategy diagnosis in 2016, the UK’s Joint Forces Command built an innovation ecosystem as a core component of its Strategy, the guiding principle of which was that “through innovation, integration, and information, Joint Forces Command will secure advantage for the Joint Force”.

The approach we chose to build our innovation ecosystem was based upon that described by Scott D Anthony (of Innosight), and others. This method was selected because it held out the prospect of “building an innovation engine in 90 days”, and of doing so without requiring large numbers of people, (though it is fair to say that Scott did not envisage his approach being taken up in the public sector!). And our innovation focus was to be on what we called a Digital Acceleration in what we christened “MilTech”, taking advantage of the digital disciplines having such an impact in the civil sector, most obviously Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy.

At the core of this ecosystem was an innovation unit, we called the jHub (the j being short for Joint).

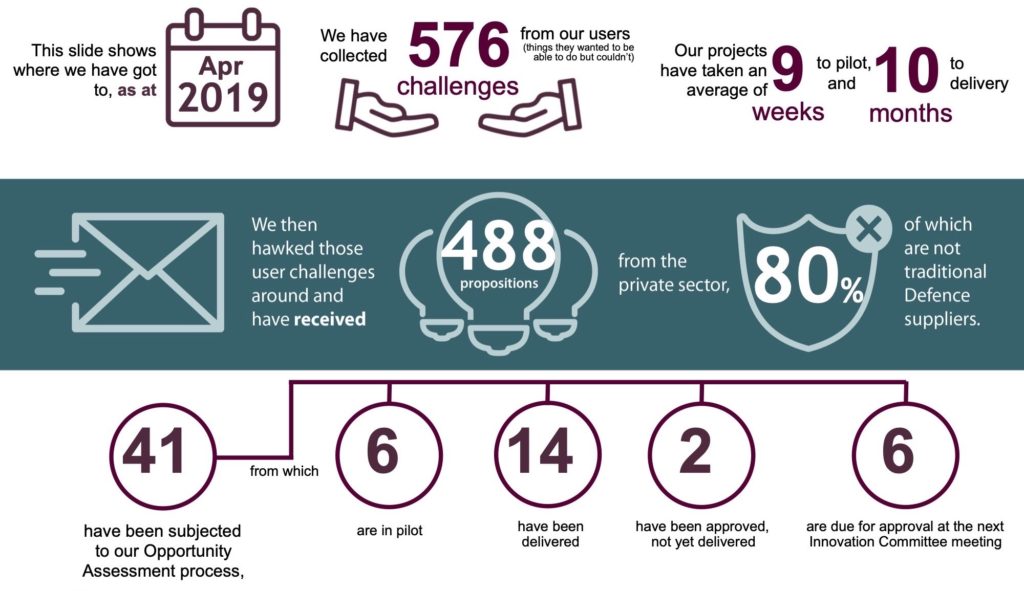

First established in September 2017, by April 2019 this unit, of less than 10 full time employees, had received 488 propositions from the private sector, some 80% of which were from Small and Medium Size Enterprises who were not traditional suppliers to Defence, mostly tech start-ups. By the time I left JFC, the jHub had subjected 41 projects to its Opportunity Assessment process, and delivered 14 projects into the hands of users, taking, on average, 9 weeks to get projects into pilot after passing through the Opportunity Assessment gate, and 10 months to Delivery into the hands of Users. This was warp speed by MOD standards, and very welcome to both start-ups and VCs, such as Animal Dynamics, Tadaweb, WeSee, Stream Defence Systems, and Google Ventures (London).

So what was the secret sauce of this successful innovation activity in a large existing business? As in any endeavour, leadership is a critical success factor. The single most important, and best decision I made about innovation in JFC was the choice of Major (now Lieutenant Colonel) Henry Willi as the head of the jHub. Whoever leads the innovation unit must be empowered, with funding under their control to place projects into pilot, without reference to the normal approval system governing the rest of the business. They should also have recruiting freedoms and the power to propose their processes. This empowerment must then be extended by the head of the unit to its members in order that they can all move at best speed.

But the innovation unit also needs the most senior Champion possible to prevent it being rejected by strong antibodies in the system that pre-dated its creation. Ideally, this would be the CEO, as it was in my case, and there would only be one level of management between the CEO and his/her innovation unit. What is essential, but a tough thing to achieve, is for the organisation within which an innovation unit sits to be “ambidextrous”, as described by Charles O’Reilly and Michael Tushman. By this they meant an organisation that continues to advance its existing business in one part, whilst simultaneously pursuing innovation in another, with the senior management team acting as the bridge and unifying factor between the two. Particularly in the early days before the innovation unit has effect, achieving this ambidexterity is a problematic, and therefore takes time and effort. This is because most of the senior management team stand to lose either people or funding or kudos or the attention of the CEO to this new upstart business unit. (For example, one thing we never achieved senior management team alignment on in JFC, at least whilst I was there, was the level of ambition we had for innovation activity in the long run).

An associated factor, often discussed by practitioners, is the choice of where to place the innovation unit within an organisation. We chose to place it at the edge, rather than outside our organisation, or in the centre of it. And I do not see how it can work any other way. If the innovation unit is completely separated from the existing business it is difficult to see how the former could ever impact on the latter. The new unit might function well as a start-up, but if the long term aim is to change the way the existing business operates, which was certainly my desire for JFC, a unit which had the freedom to develop entirely its own processes and culture would struggle later to be reintegrated with the core. Equally, a unit placed in the centre of the existing business, without the freedom to do things differently, would not get beyond sustaining innovations. The solution is to situate the innovation unit at the edge of the business, with considerable, but not total, freedom.

Another task for the whole of the senior management team is to establish what level of risk appetite it has for the innovation unit. This must be at least an order of magnitude higher than in the rest of the business, and probably more. Though some will struggle to grasp it, this risk appetite equates to a willingness to tolerate failure, which must be broadcast repeatedly and widely by the senior management team, especially in a public sector enterprise. (To begin with at least, even the members of the jHub did not act as it they really believed we meant this!). A portfolio approach to risk is essential if the innovation unit is not going to be overcome by the same caution that hampers the rest of the business.

End-to-end design of the whole innovation system is also essential, (though not on the day the unit first opens for business). For example, what are its Success Criteria? We had only one: capability/functionality delivered to users. And what about exploitation paths? Unless thought is given to routes to market, the result will be lots of pilot projects that go nowhere. Similarly, we had to think through how we would handle the requirement for competition, which is the default setting for public procurement. And the degree to which the innovation unit had to have embedded functional skills or rely on the rest of the business for support. We also had to define the appropriate time to challenge the core business to fund our innovation projects: too soon and the antibodies will be too strong and no projects will even make it into pilot; too late and the innovations never become part of the core. Intellectual Property, Governance, the crucial distinction between R&D and innovation, and how to bound what can be considered an innovation project were amongst the many other issues with which we grappled. We published a Charter covering some of these issues and other aspects a few months after the jHub opened its doors.

Location, Location, Location. When we asked our infrastructure team to find a location for the innovation unit, they scoured the Defence Estate for vacant property and offered us some options. This is how the public sector works: we tend to assume that staff and suppliers will come to us, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary! But we realised that what was needed in this case was something completely different. It had to be close to concentrations of tech businesses, with a look and feel that the latter would understand, rather than be stuck behind a wire on some remote military facility. We chose a co-working building in Aldgate East, alongside 160 other start-ups, and it was the second best decision I made about innovation in JFC. It enabled us to change our premises frequently as the jHub’s needs developed and profoundly shaped its working culture.

The location also enabled us to expand our innovation ecosystem beyond the unit, in a community of interest that included academia and the private sector. Venture Capital was key in this, introducing us to promising tech and helping us to discriminate between the hundreds of proposals which flooded our inboxes. We developed a network of VC firms that were interested in Defence (which is a small subset of the VC landscape, largely because Defence is a difficult customer for Small and Medium sized Enterprises). These VCs were keen to create the conditions in which access to MOD contracts was easier for companies in their portfolio and were therefore very supportive of what they saw in the jHub.

One of the things that the VCs could see was the close connection between the jHub and JFC end Users. This is gold-dust to a start-up which wants to improve its offering as fast as possible. (One of the difficulties in selling to large organisations is the unavoidable separation between the people that buy stuff and those that use it). Not only was our success criteria all about our Users – an important article of faith – but we also had an operating model under which Users came to the jHub to pursue projects in which they had an interest, and speed was our watchword: 52 secondees were given to the jHub by the JFC User community over its first two years, working on 20% of their time. Thus, if a start-up project passed the Opportunity Assessment it could be engaged with Users very quickly, testing and then iterating their Minimum Viable Product in a pilot. For example, in our very first project, this took less than 30 days.

A major part of the reason why the jHub was able to move so fast was its escape from the tyranny of the Requirement. In classic Defence procurement, the Statement of Requirement is one of the most critical components of the process. The production of the Requirement is intended to force the User to be very thoughtful about what is required (and why), and it enables evaluators to chose one product over another by assessing their likelihood of meeting the Requirement. Unfortunately, codifying what you want in a way that can then be subject to measurement is a time-consuming process. Worse, Users don’t know what they don’t know, and therefore tend to specify their needs using yardsticks they already understand. This conservative method is not suited to the digital age. So we decided to do away with Requirements and instead to seek Opportunities. This was highly liberating, allowing us to acquire capabilities we could not have imagined in advance.

Finally, it is worth saying something about the innovation unit itself. Keeping it small turned out to be important. This was not our expectation: in Defence we have a tendency to assume that you need lots of people if you want to have impact. But when, after a year or so, we came to make the plan to grow the size of our innovation ecosystem, we chose to replicate the team rather than to increase it in size. Our view was that doing the latter would make it a team of teams, rather than a team, with very different dynamics. At any one time, 10 or so core members, plus 20 or so seconded Users, seemed to provide the degree of agility and culture that generated results. Diversity of viewpoint was also very important in creating a questioning and curious mindset in the staff. Rank, traditionally valued in the military, was no indicator of aptitude for innovation. Indeed, the fact that the team’s average age was around 30 was a positive benefit; young people, having had less exposure to MOD’s normal processes, were less likely to assume that those processes were the only way to do things round here! And the most rewarding thing about the jHub was the manifest joy people got from working in it.

Steve Jobs is reported as having said to Apple employees developing the Mac in 1983 that “it is better to be a pirate than join the Navy”. I believe that this does not have to be true. As Proctor and Gamble and many other thriving businesses have shown, the owners of stage coaches can build railways.

I have grappled with the challenge of innovation over a 40 year career in public service, the last 15 years leading large organisations through fundamental and constant change: from the Cold War, to Counter-Insurgency Campaigns, to the resurgence of Hostile States, latterly against the background of the 4th Industrial Revolution. My experience of success and failure in this endeavour, the skills I have learnt and developed, my digital knowledge, and passion for innovation, have equipped me powerfully to help complex organisations to innovate.

I have grappled with the challenge of innovation over a 40 year career in public service, the last 15 years leading large organisations through fundamental and constant change: from the Cold War, to Counter-Insurgency Campaigns, to the resurgence of Hostile States, latterly against the background of the 4th Industrial Revolution. My experience of success and failure in this endeavour, the skills I have learnt and developed, my digital knowledge, and passion for innovation, have equipped me powerfully to help complex organisations to innovate.